Are you noticing an increase in challenging behavior in the classroom?

Every time I ask this question the answer is always a resounding “YES!”

On the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, many programs are noticing that everyone is feeling more stress, leading to unwanted behaviors in the classroom. As I visit child care centers and preschools, and during online coaching sessions, I realize there is an increase in school expulsion and child suspension. I know that administrators are not doing this lightly, because I have spoken to directors who are heartbroken every time they call a family to send a child home. Unfortunately, they feel there is no alternative, because the child is endangering themselves or others.

Why are challenging behaviors noticeably increasing? Does stress play a role? If the answer is yes to these questions, what can we do? What is our role as educators? What is our role as parents? How can we support young children? First, we have to recognize the importance of the early years and brain development. Research in early childhood education shows that 90 percent of brain development occurs in the first five years of life (Anil et al., 2002). The foundation for the person the child will become as an adult will be laid in these early years. If we want our children to grow up with executive function skills like empathy, self-regulation, self-control and impulse-control, focus, and good memory, we must create environments in which children are practicing problem solving, thinking critically and creatively, and brainstorming solutions. Our high-quality early childhood programs should be a natural place where children can practice mastering life skills (Mclelland et al., 2007). As I have been reflecting on increased behavioral issues, I came up with an analogy that helps me to understand what is going on and what the solutions might be.

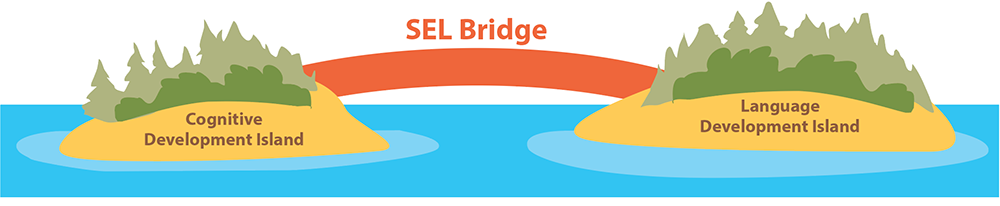

Let’s call them two islands.

On one hand, we have the “Language Island.” It contains all the research on language development, such as the importance of talking, singing, rhyming, and reading to children beginning at birth—if not while still in the womb. Educators can be more intentional with exposing children to new books, new vocabulary words, and new concepts. On the other hand, we have the second island, which we can refer to as the “Cognitive Island.” This island is all about our expectations: what do we want children to know and learn? For example, age-level milestone checklists, thematic curriculum, colors, shapes, numbers, and so on. We have all the language and curriculum research, yet we are not getting the results we want in educational foundations. Why?

In my opinion it is because these two islands are, by nature, isolated, and we need to build a bridge between them, helping us access both islands in an effective manner. This bridge is strong social emotional learning.

Strong social emotional learning, through which children can master executive function skills, can be the foundation and bridge that can access both islands. When educators know and understand brain development, and when they can implement strategies intentionally to “strengthen the bridge,” then we can give all children the best start in life. Three simple and effective strategies can get us started.

Figure 1

Strategy # 1: Teach and Model Social Emotional Learning

Modeling emotional literacy by labeling the emotions children may experience throughout the day can be very reassuring to the children as they learn to name the emotions for themselves as they are experiencing them. For example, let’s take co-regulation, when adults identify what a child is feeling and what caused it, and what can help the child in the moment. Co-regulation comes before children can master self-regulation. Regulation has three steps: 1. Identify the emotions you are experiencing; 2. Describe the cause for the emotion, and; 3. Provide a helpful solution (Erdmann & Hertel, 2019).

I witnessed a teacher co-regulate with a child effortlessly while students were working on an art activity. A 3-year-old girl was struggling with glue sticking to her fingers and she was becoming irritated and frustrated. She was kicking the table and making grunting sounds. She was trying to get the glue off. The teacher, in a very calm way, said, “I notice you are getting frustrated.” (Identify the emotion) You have glue stuck to your fingers.” (Describe the cause for the emotion.) “Would you like to take a break and go wash your hands and then continue?” (Provide a helpful solution)

In a very quick way this teacher was able to help provide co-regulation before things escalated. Role modeling showed the child how to start recognizing when she is feeling frustrated and ways to manage it. Repeated modeling of co-regulation creates safe and trusted relationships between teachers and children. This helps children master self-regulation from a young age. Allowing practice time throughout the day is key to helping children master this new skill. Practicing through play is powerful. Playing games with rules, following directions like “red light, green light” and freeze dance are all natural ways to help children not act on impulses.

Introducing the concept of self-talk, through which we can talk to ourselves and calm down (Geurts, 2018), is another effective method for teaching self-regulation. Children do not know that adults often use this strategy to talk ourselves in or out of things that we should and should not do, such as buying an expensive pair of shoes when we do not need them. We can self-talk when we are anxious about something. We must also teach children these skills.

ADVERTISEMENT

Strategy # 2: Recognizing Controlling Adults

I was very surprised to discover that rigid adults were an underlying cause of behaviors and pushback in so many classrooms and programs. I came up with a new acronym, SOS: children need to be Still, Obedient, and Silent. I hear teachers constantly repeating, “Sit on the carpet, sit on the chair, sit on your pockets, stop turning around, stop walking around.” I have witnessed teachers trying to control all the movements of the children and toys. Children cannot move freely and are not allowed to move toys from one center to the other. Teachers keep repeating waiting rules: wait for your turn, wait to speak, wait for the materials to be passed out. So much waiting! This is not natural or developmentally appropriate (Mazzoli et al., 2019). As adults we cannot sit and wait for long periods of time, and yet we expect our young children to do this for six or more hours a day while they are in school.

The expectation that children should be silent and obedient all day long for them to be considered “good and easy” is unrealistic. I keep hearing directions like, “catch a bubble,” “put your listening ears on,” “stop talking,” and” look at me.” This is not how brains are designed to learn. Teachers need to recognize the link between their “controlling” approach and increased pushbacks and power struggles. This SOS model must change.

For educators in the classroom, ask yourself, “Where can I allow children to make decisions? How many choices can I offer them during the day?” Knowing that choice equals voice is so powerful. Every time you allow children to make a choice, they are more likely to be engaged, because their voice is being heard and they are partnering in the learning process. I had one teacher share her experience after she practiced giving up some control consistently throughout the week: “We had such a good week, the stress came down and it was such a different environment. I found lots of ways to ask their opinions, but the most surprising one was during the music and movement session. They wanted to do the scarf dance. It was such a simple request, so I let them. Usually I would not bring out the scarves because I worry they will get too loud, so I avoid it. They had so much fun, we had joy in our classrooms, and they did not get loud. The best part was there were no behavior issues, and I am noticing how controlling I was, without meaning to do that. I am now going to continue implementing choices throughout the day.”

Self-awareness from educators is the first step toward making changes. A good self-reflection question is, “Am I losing control of my classroom?” Or, “Am I giving up control and giving children some agency and freedom over their environment and learning?”

Strategy #3: The Swim Coach Versus the Lifeguard

A lifeguard sits on the side of the beach scanning the beach and water, making sure everyone is safe. I see teachers doing this often. They are just keeping children safe in the classrooms and on the playgrounds. They are scanning the room for safety and policing. On the other hand, a swim coach gets in the water with a child. A swim coach watches what a child can do for themself and how to nurture that. A swim coach teaches techniques.

Let’s look at one classroom management strategy: monitoring the number of children per center. If only three children are allowed and four end up there, a lifeguard teacher would say, “Now how many children are here? And how many should be here? And who should go?” Just focusing on rules and compliance, even when there is no problem. Now, if the teacher was being a swim coach, her reaction might be vastly different. She would only walk over if there was a problem, and then use it as a teachable moment to ask the children to brainstorm and solve the issue of more children in the center than allowed. If the children say, no, we can play together, we do not want to leave, then the teacher should recognize their effort in collaborating and problem solving.

Some “classroom management strategies” end up backfiring, and instead of being used as a tool to help children master life skills, they are being used to police and control the environment, children, and play. Instead of focusing on compliance, I invite educators and directors to focus on connecting with individual children and developing genuine relationships. The more we connect the less we correct!

In conclusion, it is imperative that high-quality early learning programs include educators and administrators who understand brain development and recognize the important work we must accomplish by deeply connecting with the children in our care. Early childhood programs must actively guide and provide children with practice time to learn and master executive function skills including problem solving, self-regulation, impulse control, and collaboration.

References

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2016). Standing Together Against Suspension & Expulsion in Early Childhood. naeyc.org

Conscious Discipline. consciousdiscipline.com

Mcclelland, M., Cameron, C.E., and Connor, C.M. (2007). Links Between Behavioral Regulation and Preschoolers’ Literacy, Vocabulary, and Math Skills. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 947-59

Pahigiannis, K., Rosanbalm, K. and Murray, D.W. (2019). Supporting the Development of Self-Regulation in Young Children: Tips for Practitioners Working with Preschool Children in Classroom Settings. OPRE Brief #2019-29. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Li, P. (2022). What Is Positive Self Talk For Kids And Why Is It Important. Parenting for Brain. parentingforbrain.com

Ruhr-University Bochum. (2021). Making the wait less arduous for toddlers: Developmental psychology. ScienceDaily. sciencedaily.com

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. casel.org

Prerna Richards is a keynote, international and national speaker, behavior coach and NAEYC consultant. She has been in the early childhood education field for 37 years. She is a registered master level trainer with the Texas Early Childhood Professional Development System. Her educational philosophy is grounded in a play-based approach along with a strong social-emotional foundation. Richards is the winner of Susan Hargrave trainer of the year award from TXAEYC in 2020.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT