The expression of self is an innate ability of young children, and we see this in the many ways in which they develop different gestures as a means of communication (Longobardi et al., 2015). With one glimpse into a toddler classroom, we see a child using their words to ask a peer for space; someone else is using their fine motor skills to wave hello to a friend; another offers a material to a friend who is sad; and a small group is exploring the relationship between flowers, watercolors, and coffee filters, communicating their motivation to make meaning of their world. These gestures and more occur constantly within relationships between young children and their worlds, as they underlie this innate desire of the child to express their thoughts, feelings, and ideas (Smith, 2021).

While I was completing my master’s degree and teaching residency at Boulder Journey School, a Reggio-inspired school in Boulder, Colorado, I learned alongside a group of children who were 2.1-2.5 years of age. One particular gesture of communication that piqued my interest within this toddler classroom was that of mark-making. It was a plane of development that seemed to permeate nearly every aspect of our daily lives in the classroom, whether it was through dialogue with clay, stamping our footprints in the snow, or creating lines with a woody crayon that appeared to reach every nook of our classroom. Our broader classroom community was engaged daily in this research, asking the overarching question, “Who am I in relation to my environment?”

This sort of metaphorical mark-making—the children working to find ways to express their autonomy, to influence their environment and to feel empowered by the ways that they can bring about change—seems mystifying. Why do young children feel so compelled to engage in these experiences?

One way that I have chosen to explore this is through the specific pathway of scribbling. Why do children scribble? What are they trying to tell us through their scribbling, and what meaning do these marks hold for them? How, as educators, can we better attune ourselves to be able to truly listen to this language of the child?

Proposed theories in the existing literature include emergent literacy (Lancaster, 2007; Smith, 2021), meaning-making (Cox, 2005; Smith, 2021; Sunday, 2017), and motor babbling (Coates & Coates, 2015; de Rijke, 2019; Longaboardi et al., 2015). The role of the environment is crucial as well, and includes aspects such as socio-cultural contexts (Cameron et al., 2019; Sunday, 2017), the dynamic nature of young children’s marks (Cox, 2005; Lancaster, 2007; Smith, 2021; Sunday, 2017), and utilization of the environment as the third teacher (Lancaster, 2007; Sunday, 2017). The role of the educator is important here as well, and the literature suggests that adults should work to value the child’s process of drawing, rather than solely their product (Coates & Coates, 2015; Cox, 2005; Longobardi et al., 2015), and to centralize visible listening within teaching practices (Coates & Coates, 2015; de Rijke, 2019; Narey, 2017; Smith, 2021).

History of Research on Scribbling

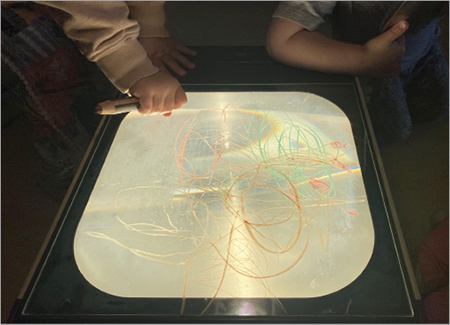

Children’s drawing can be seen as a constructive process of “thinking in action.” [©Hattie Peterson]

Throughout the history of child development research, scribbling has largely been regarded as “meaningless doodling” (de Rijke, 2019). The origins of the word scribble date back to the mid-15th century, and it is derived from the Latin root scribere, meaning “to write.” The noun scribble emerged in the 1570s, and came to be defined as “hurried or careless writing.”

To this day, our society tends to view scribbling as related to emergent writing, or mark-making that precedes legible writing of language (de Rijke, 2019). This belief can be attributed to the existing research that has been conducted over many decades, most of which describes children’s drawing in terms of psychological and developmental sequences (Cameron et al., 2019). These existing frameworks focus on the product of children’s drawings, rather than the process, and thus it is rare for young children’s drawings to be truly valued until visual realism can be discerned by an adult—which is often accompanied by praise as an indication of a developmental milestone that has been reached (Coates & Coates, 2015). This perspective disregards the child’s learning that has taken place throughout their process of mark-making over several years of their development, and does not place value on observing children in action in the early stages of scribbling (Coates & Coates, 2015).

A new wave of research has worked to reconsider the developmental stages that children undergo in their graphical representations, inviting adults to focus on the processes that children experience in their mark-making activities, rather than solely on the product (Einarsdottir et al., 2009). This research has revealed more depth and complexity in the reasons why young children scribble, and thus, there exist several different perspectives surrounding young children’s intentions in their drawing processes. Within the last couple of decades, new findings have suggested that educators carefully consider the role of the environments in which children make marks (Lancaster, 2007; Sunday, 2017), as well as the ways that educators can better listen to and honor children’s mark-making experiences (Coates & Coates, 2015; Cox, 2005; de Rijke, 2019; Narey, 2017; Smith, 2021).

The Perspective of the Child: Why Do Children Scribble?

Emergent Literacy

Throughout the existing literature, there seems to be a sort of discord surrounding the question of how scribbling intersects with early literacy development. Some research suggests that an understanding of representational principles of drawing, writing, and numbers is more likely to develop concurrently, rather than in a sequence (Lancaster, 2007). Others hypothesize that scribbling, play, and literacy are intricately intertwined (Coates & Coates, 2015)—therefore, the three cannot be separated—and that when educators focus too much on measurable basics in young children’s literacy development, the child’s innate literacy practices are disregarded (Smith, 2021). Yet another perspective argues that perhaps young children’s mark-making processes are more than just a precursor to writing, and that our view as adults is too narrowly focused on literacy altogether (Sunday, 2017).

One thing that the literature does agree on, however, is that children under 3 years old are capable of using graphic marks in highly intentional and reasoned ways (Lancaster, 2007; Smith, 2021; Sunday, 2017). Lancaster (2007) states that in doing so, they draw upon their personal, social, and bodily experiences, and construct signs and texts to represent these. The graphic signs of children are unique, in that they cannot be directly associated with or compared to any existing conventional systems (Lancaster, 2007).

ADVERTISEMENT

To Make Meaning

Children are immersed in a world full of movement and sounds, and we see the ways that they work to make sense of this through onomatopoeic scribble. [©Hattie Peterson]

As previously stated, a shift in perspective within research has moved away from describing children’s drawings in terms of developmental sequences, and instead much of the recent research now considers children’s drawings as expressions of meaning and understanding (Einarsdottir et al., 2009). Children’s early visual texts are a pathway of making meaning of their experiences in the world, not created from the purpose of making reproductions of real-world objects; this is an area in which adults should work to alter their perceptions of how children make marks (Narey, 2017).

This focus on drawing as meaning-making opposes the discourse of drawing as representation and rather focuses on the children’s intentions (Cameron et al., 2019). In this way, drawing can be seen as a constructive process of “thinking in action.” A team of researchers found that while listening to children as they drew, it was revealed that the children had involved imaginative play (Coates & Coates, 2015). They concluded that drawing, even at a scribble stage, allows the child to enter a realm of fantasy—so much so that the children were continuing a type of role-play into their drawings at a level that was not possible in the physical setting (Coates & Coates, 2015). Sunday (2017) argues that society needs to make a shift in the ways that children’s drawing processes are viewed; too often this valuable process is “marginalized, misunderstood, and underutilized” in early childhood spaces.

It has been indicated in the research that as a young child develops in their drawing abilities, they begin to “explore personal meanings through their free drawing” (Longobardi et al., 2015). Children do not see the world as static geometric figures; rather they are fascinated by its dynamic properties. They see the world through a lens of animism as they perceive things as living and “endowed with intentionality.” Where adults see “vertical, horizontal, ovoid, oblique, or spiral lines,” children feel “good, happy, playful, or bad, ugly, scary, and sad lines.” Graphical activity provides young children with opportunities to mediate important connections between their internal and external worlds, reproducing them on paper where they can be corrected and controlled (Longobardi et al., 2015).

Children are immersed in a world full of movement and sounds, and we see the ways that they work to make sense of this through onomatopoeic scribble (Longobardi et al., 2015). This type of scribble can be defined as “any trace that is accompanied, during its creation, by an onomatopoeic expression.” These marks do not appear to us as adults to represent the experience that the child is processing, but here the child concludes an important part of their graphic development because soon the line moves from representing their fantasy, to “assuming the shape of the object which it depicts.” There is still no actual representation of reality in these drawings, and the child is more oriented towards “what they have experienced with the represented object” (Quaglia et al., 2015).

After the stage of the onomatopoeic scribble, a child’s drawings begin to organize themselves into a figurative schema (Longobardi et al., 2015). Here the child artistically processes, through the subjects of their drawings, which objects they love, and which they fear. This marks the beginning of a new level of organization of their cognitive development, as children seek and find analogies between real objects and their graphical products. This happens spontaneously, as the child suddenly abandons the scribble—a dynamic representation of an object—in favor of figurative schemes which better suit their creative needs to make reality “real” (Longobardi et al., 2015).

Motor Babbling

As children are expressing their competencies in communication through the language of drawing, they initially undergo a stage of development that has been coined as motor babbling (Coates & Coates, 2015; de Rijke, 2019; Longobardi et al., 2015). Here, researchers draw a parallel between scribbling and egocentric language; the function of scribbling is a type of “graphical monologue,” (Longobardi et al., 2015) which accompanies and reinforces the child’s imagination. There seem to be simultaneous transformations between language development and development of drawing skills. As both evolve, the child is able to communicate more effectively with the world around them (Longobardi et al., 2015).

Even in children who were more pre-verbal and were in earlier stages of scribbling, researchers have noted a high level of enthusiasm and a need to communicate through making marks (Coates & Coates, 2015). These marks are initiated by a purpose in the child’s mind as an attempt to perhaps communicate in a way that is similar to the young child’s language stage of babbling, as they seek to interact with the world around them (Coates & Coates, 2015). Scribbling can also be acknowledged as a type of sensory exploration, where the child develops “feel” (de Rijke, 2019) in a social sense as well as the fingers and hands; this includes tactile-kinesthetic perception, fine motor coordination, and muscular control. It has been proposed that “just as babbling is a natural way to gain language, scribbling is a natural gateway to motor and muscle control or coordination” (de Rijke, 2019).

Role of the Environment

Children are immersed in a world full of movement and sounds, and we see the ways that they work to make sense of this through onomatopoeic scribble. [©Hattie Peterson]

The existing research strongly and unanimously agrees that young children’s drawings reflect their sociocultural context, and therefore are intricately influenced by their place in the world (Cameron et al., 2019; Cox, 2005; de Rijke, 2019; Einarsdottir et al., 2009; Lancaster, 2007; Narey, 2017; Smith, 2021; Sunday, 2017). Young children’s drawing is both a social and cultural activity, which is influenced by the beliefs of their surrounding adults and peers, as well as the environments in which the children are embedded (Cameron et al., 2019; Sunday, 2017).

Meaning is not tied to one single event, and we must recognize the ways in which meaning is both continuously shifting and is never complete (Sunday, 2017). Children might encode an idea through a mark, which they then decode in a different way; marks made by children are often fluid and can be reinterpreted many times by them (Cox, 2005). It is in these spaces, which are intersections of space, materials, and time, that they experiment with (re)working and (re)imagining their ideas (Smith, 2021; Sunday, 2017). One way in which educators can support this notion is through utilizing the environment as the third teacher, as this perspective honors the dynamic components of the drawing process (Sunday, 2017).

Role of the Educator

There is a kind of mysterious joy that can be found for me as an educator as I learn to listen to the children’s processes of mark-making. [©Hattie Peterson]

One way that educators can support young children in their drawing experiences is through what has been called “visible listening” (de Rijke, 2019). This idea indicates that the role of the educator in children’s experiences is simply to be present and to truly listen, or to be “in-tune” (Smith, 2021) with their mark-making and meaning-making processes. Within the Reggio Emilia approach, listening is seen as an “active verb that involves giving meaning and value to the perspectives of others,” (de Rijke, 2019) and values “differences, doubt, and uncertainty.” De Rijke (2019) strongly believes that visible listening is a way in which educators can honor the complex and deeply meaningful ways that children make marks. When we assess the product as isolated from the process of production, children’s visual texts do not give educators a complete picture of their meaning-making (Narey, 2017). Therefore, as adults, it is crucial that we shift our focus to the process of the way children make marks, rather than assessing the product alone (de Rijke, 2019). Educators should listen to what the children are saying, respect the child’s intellectual integrity, and reinforce that scribbling is an exciting, serious, and stimulating activity (Coates & Coates, 2015).

This literature review was brought about by the many questions and wonderings I had about the scribbling and mark-making—in both a literal and figurative sense—of the children in my class, and to be honest, I think I have concluded this research exploration with even more questions than I began with. I realize that young children’s scribbling processes and development are even more complex than I had originally thought.

There is a kind of mysterious joy that can be found for me as an educator, though, as I learn to listen to the children’s processes of mark-making. Because the children in my care are in very early stages of development of language and vocabulary, it can be difficult to truly understand what they are drawing, and why. I can accept that I may never fully know the child’s intentions of their scribbling activities, and I may not always be able to interpret what their marks mean to them. Lancaster (2007) models an embracing of this beautiful mystery, and suggests that what truly matters as educators is that we are simply able to be present with the children as they engage in these complex processes.

References

Cameron, C.A., Pinto, G., Stella, C., and Hunt, A.K. (2019). A Day in the Life of Young Children Drawing at Home and at School. International Journal of Early Years Education, 28(1), 97–113.

Coates, E. and Coates, A. (2015). The Essential Role of Scribbling in the Imaginative and Cognitive Development of Young Children. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 16(1), 60–83.

Cox, S. (2005). Intention and Meaning in Young Children’s Drawing. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 24(2), 115–125.

de Rijke, V. (2019). Steiner, Eurythmy and Scribble: Visible Music and Singing, Visible Speech and Listening. Art and Soul: Rudolf Steiner, Interdisciplinary Art and Education.

Einarsdottir, J., Dockett, S., and Perry, B., (2009). Making Meaning: Children’s Perspectives Expressed Through Drawings. Early Child Development and Care, 179(2), 217-232.

Lancaster, L. (2007). Representing the Ways of the World: How Children Under Three Start to use Syntax in Graphic Signs. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 7(2), 123–154.

Longobardi, C., Quaglia, R., and Iotti, N.O. (2015). Reconsidering the Scribbling Stage of Drawing: A New Perspective on Toddlers’ Representational Processes. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–9.

Narey, M.J. (2017). The Creative “Art” of Making Meaning. In Multimodal Perspectives of Language, Literacy, and Learning in Early Childhood (pp. 1–22). essay, Springer International Publishing.

Quaglia, R., Longobardi, C., Iotti, N.O., and Prino, L.E. (2015). A New Theory on Children’s Drawings: Analyzing the Role of Emotion and Movement in Graphical Development. Infant Behavior and Development, 39, 81–91.

Smith, K. (2021). The Playful Writing Project: Exploring the Synergy Between Young Children’s Play and Writing With Reception Class Teachers. Literacy, 55(3), 149–158.

Sunday, K.E. (2017). Drawing as a Relational Event: Making Meaning Through Talk, Collaboration, and Image Production. Multimodal Perspectives of Language, Literacy, and Learning in Early Childhood, 87–105.

Hattie Peterson is just starting her career in early childhood education. She holds a bachelor's degree in human development and family studies from Colorado State University, and recently obtained her master's degree in learning, development, and family sciences from the University of Colorado Denver. She is a Colorado native and now teaches at the Aspen Center for Child Development in Longmont, Colorado, a nonprofit early learning center. She learns alongside a classroom community of older toddlers, where she gets to live out her passion of making the Reggio Emilia approach accessible to all children and families.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT