While we often think of loose parts as “stuff,” Simon Nicholson’s original theory actually contains additional sound educational principles beyond the material options. Nicholson advocated for children’s involvement in their own education, using the environment as part of the learning process, putting experimentation at the core of understanding, and inviting application to real world problems. Children in our care benefit from these principles as well.

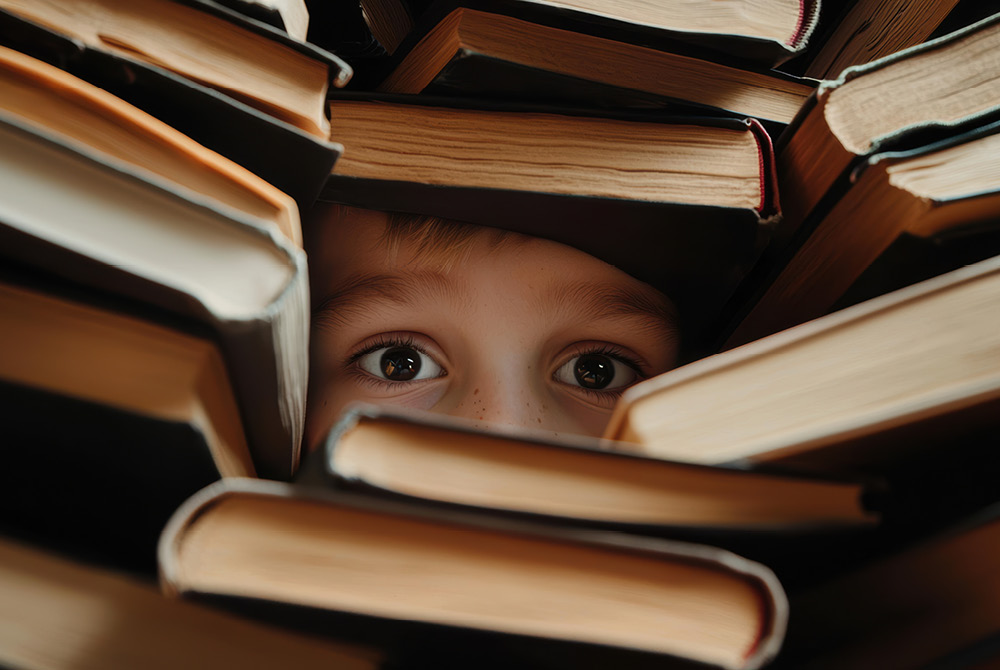

Children’s Involvement in their Education

Nicholson (1971) suggested that we should decrease the restrictions and limitations around children’s play and investigations. He mentioned, “Young children (often) find the world incredibly restricted—a world where they cannot play with building and making things, or play with fluids, water, fire, or living objects, and all the things that satisfy one’s curiosity and give us the pleasure that results from discovery and invention.”

While we may not be playing with fire in many settings, allowing children to explore the world around them helps develop a sense of wonder and awe. Having a “yes” environment, in which we do not restrict children’s curiosity, helps them develop and grow. Intentionally setting up our spaces for less restriction includes using an open, flexible floor plan, where materials from one zone can move to another zone. Of course, there can be parameters and times we need to say no, but if a desired action is not hurting the child or space, consider allowing more freedom and curiosity.

Nicholson (1971) also offered that children should be directly involved in using, planning, and even building our spaces and learning. Nicholson stated, “Most environments that do not work, such as schools, playgrounds, child care centers, and museums, struggle because they do not meet the ‘loose parts’ requirement. The adults (artists, landscape architects, planners) have had all the fun playing with their own materials, concepts, and planning-alternatives, and then the builders have had all the fun building the environments out of real materials. Thus, by the time children occupy the space, much of the fun and creativity have been stolen.”

Should we undertake all the planning of our spaces, or might we allow our students to have fun and be creative within their environments? Large loose parts allow children to recreate and build their spaces regularly. Crates, large fabrics, blocks, planks, stumps, and other loose parts can be rearranged infinite times for a new space. (The book “Roxaboxen” shows how children transform their outdoor space over time using the materials around them without adult directed plans.)

Environment as Part of the Learning Process

When thinking of our learning spaces, Nicholson (1971) advocated for using our spaces for both learning and play. I often refer to this as blurring the lines between inside and outside. He mentioned, “By allowing learning to take place outdoors, and fun and games to occur indoors, the distinction between education and recreation began to disappear.” Often, we think of our outdoor spaces as only for recess or breaks; however, children have so many opportunities to learn and discover outside. We can, in tandem, allow time for fun indoors, which is often seen as a more academic space.

We have gotten to know the trees that surround the building, returning frequently to one evergreen that has enough open space to play and explore.

We might also explore beyond our typical play spaces outdoors to look for additional opportunities. At one preschool I visit, we have gotten to know the trees that surround the building, returning frequently to one evergreen that has enough open space to play and explore below, with plenty of natural loose parts. As we read various books about animals in trees, this tree became our haven to explore. One teacher remarked, “I have been teaching here 13 years and never noticed this tree,” yet it reminded her of playing in the bushes as a child. Get to know your outside spaces as a class, and embrace the loose parts you might find right under your nose!

Nature can also be a part of our inside spaces—large windows with a view of nature, bird feeders, a pollinating garden, and a watering station can benefit us both outside and inside. Many natural loose parts can also come inside as part of our classroom options. Pinecones, rocks, sweet gum balls, sticks, tree cookies, and other local natural options can be good inside loose parts.

Additionally, our spaces can be arranged in a manner that invites children to experiment and learn things for themselves. Nicholson (1971) wrote, “Children learn most readily and easily in a laboratory type environment where they can experiment, enjoy and find out things for themselves.”

This is not a stuffy laboratory with white coats and exact procedures, but one that allows for learning and understanding through experimentation. We love visiting interactive museums as a family—could our learning spaces be more like a science museum with wind tubes, building materials, and ramp walls? In our space, children know they can experiment and explore the materials available. They learn through their interaction with these materials.

Experimentation at the Core

Nicholson (1971) also mentioned that children should be involved in their learning through experimentation. He noted, “The study of children and cave-type environments only becomes meaningful when we consider children not only being in a given cave, but also when children have the opportunity to play with space-forming materials in order that they may invent, construct, evaluate and modify their own caves. When this happens we have a perfect example of variables and loose parts in action.”

ADVERTISEMENT

It is wonderful to have real-life experiences, such as visiting a cave or other space in nature. And it becomes very meaningful as children take the next step and construct their own spaces as well. Nicholson also commented on the vast ways children can interact with concepts and loose parts around them: “All children love to interact with variables such as materials and shapes; smells and other physical phenomena, such as electricity, magnetism, and gravity; media such as gases and fluids; sounds, music, and motion; chemical interactions, cooking, and fire; and other people, animals, plants, words, concepts, and ideas. With all these things all children love to play, experiment, discover, invent, and have fun. All these things have one thing in common, which is variables or ‘loose parts.’”

Opening our eyes to a broader range of loose parts can make an impact in our classrooms. While safety parameters should be considered, playing around with a variety of concepts such as magnetism, electricity, words, sounds, and motion, rather than just tree cookies, rocks, and cardboard boxes, can help our students develop their own understanding of and curiosity in the world. I recently watched a child explore the sound properties of a holiday bow, mashing the different loops to produce a variety of sounds. This same child experiments with sound capacity of a variety of materials on a regular basis. In a “Loose Parts Nature Play” podcast episode, I shared the following tips for turning a learning experience into a loose parts discovery session.

- Allow experimentation. Get rid of the “recipe.”

- Pause for observation, wonder, and awe.

- Follow the child’s lead. “I wonder if…”

- Ask children how they might extend and explore this more. What might they use next time? What other ways might they experiment and explore?

- Leave materials out, if possible, to allow for additional experimentation.

- Document the experience with photos, journaling, and capturing the inquisitiveness.

- Be open to other exploration.

- Let the learning emerge rather than telling how it should happen

(Gull, 2021).

I love discovering alongside children. While exploring electricity with slightly older children, this approach led to new information about circuits that I did not know either! We were able to go beyond “book learning” to experiential learning with the loose part of electricity.

Real World Application

Another concept of the theory of loose parts is their utility for solving real life problems. Nicholson (1971) encouraged us to look at problems right around us as he stated, “Environmental education means the total study of the ecosystem, i.e.: man, his institutions, and his structural, chemical, etc., additions, included. The subject of human ecology, our values and concepts, the environmental alternatives and choices open to us, in the fullest sense, has recently become a dominant factor in some education programs. In the simplest possible terms, the most interesting and vital loose parts are those that we have around us every day in the wilderness, the countryside, the city.”

Loose parts may look different in every setting, as we embrace the unique characteristics of our own students, climate, natural resources, and environment. Using a place-based approach with local loose parts allows children to get to know the area around them. Additionally, Nicholson promoted children being involved in a process to solve problems. He wrote, “Children greatly enjoy playing a part in the design process. This includes the study of the nature of the problem; thinking about their requirements and needs; considering planning alternatives; measuring, drawing, model-making and mathematics; construction and building; experiment, evaluation, modification and destruction.”

This approach of understanding the problem and working toward plans is similar to the engineering design process. We have adapted this to a loose parts cycle in our book “Loose Parts Learning in K-3 Classrooms.”

While this may not look like a formal process, think back to a time when you observed a child exploring something new. One child I observed became curious about yarn after we read the book “Seaver the Weaver.” He imagined the possibilities and experimented with yarn in a few places in the outdoor space. He played around with how the yarn worked around the fence. He improved his design and shared it with others around him. His mom mentioned he asked for string while playing later at home, starting the cycle again.

As we refine how we use and present loose parts in our space, let’s include the children more in their own education, use the environment as part of the learning process, allow experimentation to be the core of children’s understanding, and encourage application to real-life problems. These core principles of the theory of loose parts will serve our students and communities well, and foster imaginative, intriguing exploration by our youngest learners.

References

Gull, C. (Host). (Loose Parts Nature Play. (March 15, 2021). Color Exploration [Audio podcast episode]. In Loose parts nature play. loosepartsnatureplay.libsyn.com

Gull, C., Levenson Goldstein, S., & Rosengarten, T. (2021). Loose parts learning in K-3 classrooms. Gryphon House, Inc.

Nicholson, S. (1971). How not to cheat children – The theory of loose parts. Landscape Architecture, 62, 30-34.

Dr. Carla Gull is an online instructor for beginning courses at the University of Phoenix. She has been in education for over 20 years and hosts the Facebook group Loose Parts Play and the podcast Loose Parts Nature Play. She leads professional development and academic research in outdoor classrooms, loose parts, tree climbing, and nature play. She facilitates classes with Tinkergarten and leads local nature and environmental education programming. She is coauthor of the book, "Loose Parts Learning in K-3 Classrooms." She loves going on adventures with her four boys.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT