Student: Let’s get the bad guys! Let’s put him in jail. (Students pretend to shoot guns and run around frenetically.)

Teacher: Friends, wait, stop. Who are bad guys?

Student: Bad people.

Teacher: Hang on. Let’s all sit down. Do you remember we talked about this? Who are bad guys really?

Student: People who make bad choices.

Teacher: That’s right. There are not bad people, just people who have made bad choices. We all make some bad choices, and we can always try to make better choices.

This is a discussion between 3-year-olds and one of their teachers about their fascination with “putting bad guys in jail.” This is a topic that is constantly in the news and our cultural discourse. Unpacking children’s understanding is a part of our effort to be an anti-bias anti-racist school that helps children avoid forming hurtful and harmful stereotypes about the BIPOC community.

Committing to the ABAR Curriculum

Located in a predominantly white suburb of Boston with a primarily white student population of 3- to 6-year-olds, the administration and teachers at our school wanted to think through our role in the systemic racism in our country. Can a school offer an ABAR curriculum effectively in such a setting? We are working in our school community to create curriculum to reflect our beliefs, but there are challenges, and our anti-racist education is a work in progress.

In the spring of 2020, it became crystal clear that early childhood educators had an invaluable opportunity to make sure our youngest learners began their education exploring anti-bias and anti-racism. Before the Black Lives Matter protests, our school had been pushing to change how we approach our BIPOC students, families, and curriculum material. However, the need to make changes became urgent. Unless adults specifically intervened, preschool-age children were starting to form racist and biased opinions just by looking around at the world. Until recently, most white parents and teachers thought if they did not mention race and treated everyone with kindness and respect, the children in their care would not be racist. The privilege of being white allows white teachers and families to fall into thinking, “Well yes, people can be racist, but we are not so we do not have to worry about it.” It is a privilege to choose not to discuss race. This is the “colorblind” approach to socializing children. It does not work (Katz, 2013).

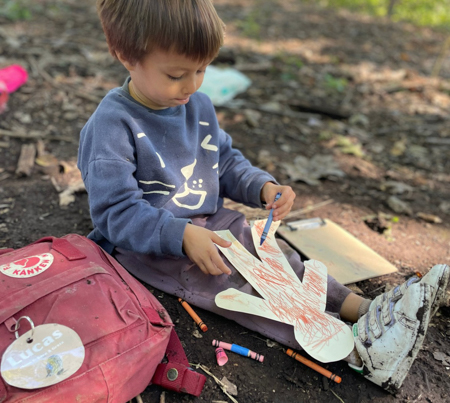

This learner works on an image of himself to display with his family photos. [©Apple Orchard School]

The current consensus is it is never too early to start conversations about race with young children: research shows that babies notice race as early as 6 months old; 2- to 4-year-olds internalize racial bias; 5- to 8-year-olds make racial value judgments, by age 12, children have formed a complete set of stereotypes about every racial, ethnic, and religious group in society (Dulin-Keita, Iii, Fernandez, & Cockerham, 2011). In the preschool years, white children begin to learn the power codes of racism and to develop internalized racial superiority (Derman-Sparks & Ramsey, 2002).

Certainly, it helps to expose students to people of all races, in many different kinds of environments and roles. However, our school does not provide a diverse backdrop of students. While we lack diversity, we still believe talking with children directly about race is critical.

Dedicated Time to Talk

We create a family wall of photos that remains up the entire year at student eye level, so that students feel connected to each other. [©Apple Orchard School]

We use these guidelines when we come together to talk about topics that are difficult, emotional, and triggering around race.

Community Conversation Group Norms (Taken from AISNE)

- Honor confidentiality.

- Speak from the “I” perspective.

- Listen to understand vs. listen to respond.

- Accept the speaker’s viewpoint as true for the speaker in the moment.

- Manage both intent and impact.

- Be fully present.

- Take risks and participate.

- Lean into discomfort; be willing to have the tough, candid, caring, courageous conversation.

- Accept non-closure.

Ensuring All Voices are Heard

How do you do the work of challenging your systems without making others feel badly about the mistakes they make? This is accomplished by repeatedly confirming and sharing how we all make mistakes and owning them, asking ourselves what small or big way we are trying to do better and be better, seeking out resources, and taking clear action. For example, one of our white teachers is enthusiastic and passionate about educating her students and has been doing it exceedingly well for 30 years, yet she was worried when she realized during our affinity group work that she has said and done things that she now knows are racist, for example, promoting songs and rhymes with racist origins. Teachers voiced they too realized their mistakes in the past and we applauded her research and effort to remove songs that created hurt for BIPOC people.

Understanding Similarities and Differences

We start the year with a letter to parents asking all sorts of information about their child and their family to foster a good connection. We create a family wall of photos that remains up the entire year at student eye level, so that students feel connected to each other. White children first need to explore the breadth of differences and similarities among white people. There is always diversity in a classroom, and it needs to be noted and celebrated. This is often best done through noticing and describing physical attributes. We strive to foster self-confidence in everyone. Teachers need to be very intentional in their responses and language, as is demonstrated by a moment that happened one autumn. A class was painting a mural on a large piece of bark. The kids were shouting out the colors they wanted and one teacher was squeezing out paint.

“Pink!”

“Blue, please!”

“What about black?”

The teacher paused for a second and thought out loud, “Hmmm, well the bark is already really dark so I do not think we need any black paint.”

She reinforced, unconsciously, the belief that black is not a necessary color. Her co-teacher quickly stepped in and said, “Sure, we can use black,” and squeezed some black paint along the bark.

If her co-teacher had not spoken up, it would have been a moment for a child to make the connection that, “Well, my teacher does not use or like the color black, it must be a bad color.”

[©Apple Orchard School]

Integrating Anti-Racist Thinking

As we have focused on “doing the work,” we have often wondered what that means in terms of day-to-day curriculum for young children. A video platform can be a wonderful way to invite authors, artists, or musicians of color to share their story live to children. This provides modeling of people of color in powerful roles and as valued contributors to our students’ learning.

Invite all parents to spend time with your class, either by sharing an activity or just spending a few hours. This naturally brings parents of color into the classroom.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nature Helps ABAR Work

Teacher awareness and understanding about anti-racist curriculum becomes critical. A teacher response of, “Yes, Elaine’s skin is darker. Your eyes are brownest. And Melissa is tallest,” helps normalize body differences.

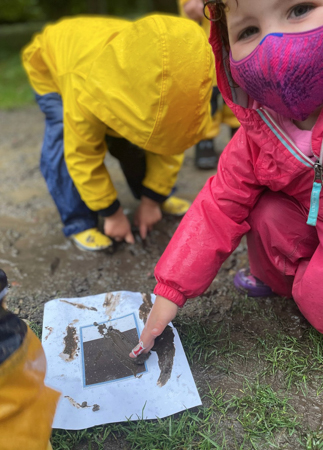

The teacher can also ask, “What other skin tones do you see?” [©Apple Orchard School]

Challenges

One of the challenges, when there are so few children of color in classrooms, is tokenism. If there is only one black child in a class, how do you talk and teach about skin color and difference without making that child feel burdened and scrutinized? When everyone puts their hands into the circle and there is only one clearly dark-skinned person, what does the teacher say?

Four-year-olds will point out, “Only Elaine has dark skin in our class.”

Who wants to be the only one? No one. This is where teacher awareness and understanding about anti-racist curriculum becomes critical. A teacher response of, “Yes, Elaine’s skin is darker. Your eyes are brownest. And Melissa is tallest,” helps normalize body differences. The teacher can also ask, “What other skin tones do you see?”

The teacher shares, “I think my skin tone looks like cinnamon and cocoa,” urging students to chime in about their own skin.

Universal Joy and Belonging as a Unifier

[©Apple Orchard School]

For example, in one of the 3-year-old classes, children read a story called “Love is …” by Diana Adams, which is about a girl who happens to be Black who finds and rescues a duck. The book describes the love the girl has for her duck. At the end of the story, the girl must let go of the duck so it can be happy in a pond with other ducks. It is a simple story about loving a pet from the perspective of a young Black girl. All the white girls and boys in the class know, and want to share in, that feeling of loving something so much. This moment of joy sticks in their brains, and they want to read again and again about this Black girl’s love for her pet. This is not a direct conversation about race—although were a question asked about race the teachers would directly address it—but it is about the love all children know for a pet. It emphasizes a universal feeling that children of all races and religions can share, and thereby shifts the focus from what is different to what is the same about us.

Mistakes are Inevitable!

Thanks to children’s book author Joanna Ho, we have realized two important subtleties in the work to become an anti-racist school. She makes two critical points about schools falling into two ways of being where we think we are anti-racist, but are in fact superficial approaches to true anti-bias thinking.

Her first point: what do we mean by difference? When we say we “embrace difference” and “celebrate difference,” that is certainly a positive message for young children, but it has a deeper implication. To say it is okay to be different assumes there is a norm, a way of being that is “just right” and “acceptable.” It is okay to be different … from what? From whom?

There is an underlying assumption that there is a perfect or acceptable way of looking or being. When you are loud or emotional, or angry or Black or brown, it is okay to be “different” from the ideal that has usually been white, calm, and male. What we are moving toward is a belief that everyone is unique and beautiful; being yourself is just the right way to be. We want to break through the idea that there is white normality. The conversation with children is that all body shapes, sizes, colors are beautiful. No one is better than another.

Ho also notes that activism is normal for young children. We believe that empathy and kindness are critical social-emotional skills for young children to develop. In fact, some of our classes have just one expectation: be kind. From that mantra stems all other class expectations. However, Ho shares why being kind is just not enough. It is too passive. We need critical thinkers and those who act and speak out to change the notion of a “white ideal.” This is a time for action, not for bystanders. While being kind is critical to our care of each other and the animals that are integral to our curriculum, it is not bold enough. We want our children to speak up and act on perceived unfairness, unjustness, or hurt, and for adults to help them figure out how to take action.

A typical example of activism at our school is when the children saw dead turtles on the road and noted that cars and tractors were hitting them. Teachers urged the children to brainstorm ways to help the turtles. The students chose to make a sign that we placed on a tree for parents and farmers to see: Turtle Crossing. Slow Down!

At the preschool age, activism needs to start small, with something that directly impacts children’s lives. For example, one class noticed trash in the frog pond. This reminded them of the book, “We are Water Protectors,” by Carol Lindstrom. They learned about Little Miss Flint, Amariyanna Copeny, who is a real-life water protector and child advocate working to bring clean water to Flint, Michigan. The class brainstormed ways they could get the trash out of the water. The student solution was to take their frog nets, scoop out the trash, and put it in the dumpster.

Below is a list of specific ways in which we are changing our community to promote racial awareness and other forms of equity. ABAR work is not a checklist; ABAR work is a mindset.

- Made clear in our ads and on our website that we have scholarship dollars for families who cannot afford our tuition.

- Changed many places on our website to reflect our commitment to an anti-bias and anti-racist education.

- Established monthly teacher affinity groups.

- Established family photo boards that remain visible all year for children to see that families come in all kinds of colors, shapes, and sizes.

- Asked teachers to consider using their pronouns on their school signatures.

- Moved parent conference sign-ups and actual conferences on Zoom, to accommodate dual working families.

- Invited nationally-recognized speakers to talk to our teaching team and parents about diversity, equity, and inclusion.

- Purchased dolls and toy people that represent a multicultural experience.

- In all new teacher interviews, we present our commitment to anti-racist education and ask applicants what their awareness and experience has been around developing and supporting an anti-racist curriculum.

- Enhanced our library with over 200 children’s books about race, and books portraying children and adults of color in varied roles. Created a section for parents and teachers in our library with books dedicated to race.

- Incorporated direct discussions about race during parent-teacher conferences.

- Created a free after-school program for BIPOC families selected from within the local public school system.

References

Derman-Sparks, L. and Ramsey, P.G. (2002). What If All the Kids Are White? Multicultural/Anti-Bias Education with White Children. NAEYC. teachingforchange.org

Dulin-Keita, A., Iii, L.H., Fernandez, J.R., and Cockerham, W.C. (2011). The Defining Moment: Children’s Conceptualization of Race and Experiences with Racial Discrimination. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(4), 662–82. doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.535906

Dunham, Y., Baron, A.S., and Banaji, M.R. (2008). The Development of Implicit Intergroup Cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(7), 248–53. doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.006

Katz, P.A. (1978). Modification of Children’s Racial Attitudes. Developmental Psychology, 14(5), 447–61. doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.14.5.447

Katz, P.A. (2003). Racists or Tolerant Multiculturalists? How Do They Begin? American Psychologist, 58(11), 897–909. doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.11.897b

Katz, P.A. and Kofkin, J.A. (1997). Developmental Psychopathology: Perspectives on Adjustment, Risk, and Disorder. In Race, Gender, and Young Children, edited by S.S. Luthar, J.A. Burack, D. Cicchetti, and J.R. Weisz, 51–74. Cambridge University Press.

Katz, P.A. (2013). The Acquisition of Racial Attitudes. In Towards the Elimination of Racism: Pergamon General Psychology Series. Pergamon Press Inc.

Human Rights Campaign Foundation. (n.d.). Key Insights from the Research on Reducing Prejudice and Bias in Children-Summary. welcomingschools.org assets2.hrc.org

Love, B. (2019). We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Beacon Press.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT