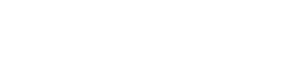

It is a cloudy Tuesday and Lucas and Jabari are hard at work near the waterside. Each is pursuing their own goal: Jabari is planning to catch minnows and Lucas is in search of frogs. Both children wish to capture, but their intended quarries and methodologies are entirely distinct. For some time, the two work amiably in parallel. Lucas leans down with care and attention over the murky waters of the bayou. Jabari kneels and searches the water with his eyes. Jabari seeks to corner the minnows using leaves and sticks, while Lucas positions his hands above the rippling surface of the water, prepared to move swiftly at the first sign of motion. Adjacent to these two, other children are busy making muddy meals and rocky soups served with sides of cloudy water. This does not, however, deter or distract Jabari or Lucas. They remain in asynchronous symbiosis for some time.

[©Ron Grady]

That is, until Lucas catches a frog.

Although the frog quickly escapes, the satisfaction Lucas feels is evident on his face. His goal has been achieved.

Then, he remembers something—and decides to share it aloud:

“Raise your hand if you remember when we built a river with James!”

What is the role of memory in children’s lives?

Anecdotally, it is not uncommon to hear caregivers and families remark about the ways that children’s memories simultaneously confound and astound them. The same 6-year-old who forgets, every day despite reminders, to put her water bottle into her bag after taking a drink can still, somehow, accurately remember scenes from the road trip she took when she was 2 years old that even her parents have long forgotten. Children’s memories, and the role that narrating these memories plays in development and consolidation of identity and in children’s social relationships, are the subject of much study and theory (Engel, 1995).

However, this story revolves around these two children at the waterside—and so it is there that we return.

“Raise your hand if you remember when we built a river with James,” Lucas declares. Most of the children do not, as they were not present. This arrow, however, so to speak, hits its target directly. Jabari indicates that yes, he does remember the river-building.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lucas goes on to suggest that they should “build a river like last time,” Jabari agrees. However, Jabari remains kneeling at the waterside, still looking into the murky shallows.

The memory of the previous time, the old goal, stirs Jabari but only momentarily. Only enough to get him to agree that building a river is a good idea, but not so compelling that he should abandon his goal. In what ways, we can wonder, might memory and circumstance intersect and interact to influence a child’s action in the present moment?

When will a memory inspire a child to pursue a course of action that diverges from an ongoing pursuit? When is that same memory not enough of an impetus? How might this be influenced by a child’s beliefs about their pursuits? Would Jabari have reacted differently to Lucas’s invitation, for example, if he had already caught a minnow? Does Jabari’s choice have to do with the fact that he believes catching a minnow is close at hand? Would the memory of another positive experience working with water in the same location have led him to a new task? What about his own desires in this moment keep the memory of building a river from moving him to immediate action and, in the same way, inspire his friend to suggest a new course?

Whatever the answer to these wonderings, the fact remains that Jabari’s body does not move. He has seen a great many minnows today, but has captured none, and he believes himself fully capable of doing so.

Lucas, in contrast, is already in motion gathering the necessary river-building supplies from our bin of waterside tools. These tools are, mostly, recycled plastic containers and trowels and shovels. As Lucas gathers, the flow of the memory throughout his mind continues. He shares that when the children worked on the river with James, “[w]e made it down here but […] we didn’t make it into the water.” I nod my remembrance and Jabari offers his “Yes,” still without moving.

This glimmer of a child’s long memory for experience in the forest intrigues me. Last year’s experiences (Lucas’s solo frog-catching and the group river-building) have each moved from the realm of lived experience to memory and, in a similar physical location and social context, these memories have been re-activated and even transformed into both a challenge and an inspiration for their current tasks.

[©Ron Grady]

Not long after Lucas begins to build the river, however, Jabari joins in. Whether he is drawn in by the settling of memory, or by the desire for connection, or if he simply changes his mind is impossible to know. However, what does become clear is that even though these two friends are now working on a new task, Jabari has not abandoned his individual intention. Yes, there is a new, unified end; but its engine (for one of the participants at least), is messy, murky, and as complex as the ecosystem of the water near which the children play.

Time reveals that for Jabari, this new task is an evolution of his minnow-catching technique. Every dig he makes with the shovel is still oriented toward this original intention while simultaneously in service of the new one. Jabari intends to capture the fish in the little inlet of river he has carved out.

“Hey, look, putting a stick here makes [water] come under and then go out,” Jabari says.

“Whoa!” Lucas is surprised, “Cool Jabari,” he supports his friend.

“I’m gonna catch the minnows in here,” Jabari remarks.

Interestingly enough, Lucas’s sharing of this memory serves as a skillful, likely intentional, technique for social connection. The building of the river satisfies his desire to connect with a friend in mutual play. He does not mind that the intention of their mutual work shifts from his initial suggestion that the two make a river that reaches the water from some nearby tree roots. For him, the connection with a close friend in this way is enough. The memory of the river building, and the present intention of minnow-catching have combined to provide an opportunity: the creation of a new memory, one that borrows from the past and evolves along the path of present interest into a novel future.

Our work with young children invites us to be both witnesses to the events of their lives and eager supporters of their interior journeys. As such, it is important for us to honor the nuance in the minutiae of the everyday. The ostensibly mundane. Through a consistent acknowledgement of what Curtis calls “children’s lively minds at work” (2017)—even and especially in these mundane moments—we cultivate the ability to honor the true nature of each child’s journey with the reverence it requires. That is, the journey of living and expressing themselves as expansive, creative individuals in the world.

References

Curtis, D. (2017). Really Seeing Children. Exchange Press.

Engel, S. (1995). The Stories Children Tell: Making Sense of the Narratives of Childhood. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Ron Grady is an early educator with a passion for child-centered and constructivist pedagogies. He encourages children to learn through art, nature, and play and enjoys exploring the ways that these connect to deep processes of creative, personal, and academic inquiry. Grady taught preschool at NOLA Nature School, and now is a first year Ph.D. student in education at Harvard University. See more of his work at childology.co.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT