[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

With help from her older brother Youalechkatl, Spirit of Tlaloc, age 7, writes:

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

I have learned Hollyhocks can be eaten (a flower that grows in the garden). When you eat them, it can help improve your breathing and clear up sinuses. I also saw a mulberry tree for the first time in Arizona, and ate its fruit.

Spaces of Opportunity also has a local farmer’s market every Saturday morning. The market has helped my 11-year-old brother named Youale to expand his plant-based business and meet great people that have become our family. Youale also helped build the high tunnel at the garden. One thing I would like to see in the future is people being able to camp and cook out at the garden.

If we travel across time, the history of human beings in what we now know as south Phoenix (also known as South Mountain Village) begins with the Huhugam peoples, who farmed this soil 1,700 years ago in the Salt and Gila River basins, and whose descendants are still farming, in spite of the dams built by the colonizers that diverted life-giving water from their fields, and later development that paved over much of the land.

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

A web of projects helps us build hope through action in a hyperlocal context, all while incidentally and intentionally addressing the causes of our global crises. With a community representing at least eight countries of origin and seven native languages, our greatest collective hope at Spaces lies in the children and the schools around us; we long to see a paradigm shift in the delivery of curriculum and enhanced understanding of the value of place-based and project-based learning. Global warming; decimation of the biodiversity of animals, insects, and plants; food apartheid; discrimination and racism; and economies designed for the ultra-rich are all addressed through Spaces’ work, and provide a unique and expansive curriculum for our children—from soil love to seed, to harvest, to community, to school, to table, to composting food waste and back again.

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

Spaces for Children

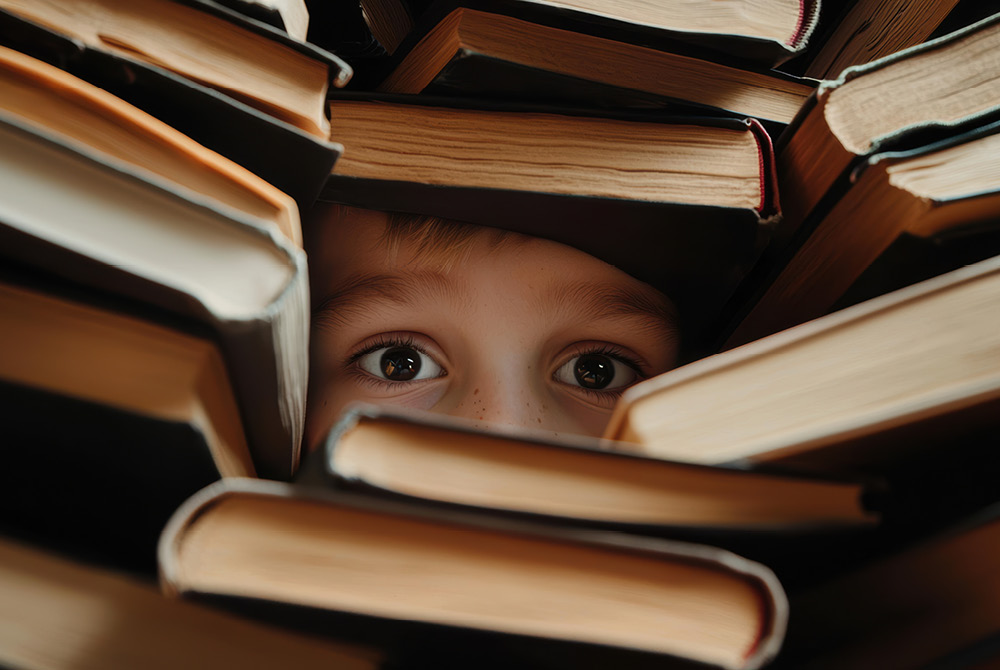

Children find their way to Spaces via many pathways—they are free to visit the outdoor classroom anytime, as there are no walls. Families visit to buy food and crafts from the farmers’ market adjacent to the outdoor classroom or to take classes on health and nutrition. School groups come from the four nearby schools—and beyond—for outdoor learning and exploration. Children come along and help when their parents or grandparents work in the fields, food forest or market, taking breaks to play. They join Be and Amy’s Project Roots kids’ gardening classes, which often seem to include exuberant dance trains through the outdoor classroom. And, children come along when families join classes and singing groups or watch cultural performances. In these ways and more, Spaces is expanding and deepening how and where children learn and grow.

School district teachers and administrators, working together with community leaders at Spaces, constantly ask, “What are we doing to support our children throughout this learning process?” Considering what we know about hands-on and collaborative learning from thinkers like Lev Vygotsky, we aim to provide opportunities to play and explore with peers of all ages. Knowing that physical and mental well-being are critical to learning, we aim to foster overall good health,

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

- Strengthen partnerships to collaboratively empower south Phoenix youth in wellness and the science of health in an outdoor setting;

- Support children, educators, and parents with the “seed to table” initiative, to foster deeper understandings about nurturing gardens, share traditional experiences, and prepare food with nutritional value;

- Develop and sustain an ongoing partnership with neighboring schools to co-design STEM curricula, support on-site learning experiences, and engage students in project-based learning.

We recognize students learn through social interactions, and so we have mobilized our community in south Phoenix to establish programs to foster this learning and support our children with ideas to solve real-world problems. By establishing an outdoor classroom in south Phoenix, we are reinforcing the need for our children to explore, learn, and share with others in a natural environment. This is a special, innovative environment that serves as the cornerstone of the South Mountain Village community as formally titled by City of the Phoenix Planning Commission.

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

From the Present to the Future

Aline, age 7, was with her grandmother, a member of Unlimited Potential, at a recent gathering at Spaces of Opportunity. As the only child in the group, she quietly raised her hand to open a conversation about our hopes for the recently completed outdoor classroom. Upon receiving the talking stick, she said, “We need a treehouse in Spaces of Opportunity.” Asked to say more, she said that treehouses make you feel brave, and “if you are afraid of heights, you need to keep trying so you can conquer your fears.” She paused and added, “But we need to have patience, too, for the trees to grow.”

Aline’s words epitomize the potential of this community, by articulating a powerful vision for the outdoor classroom and the entire Spaces of Opportunity: a place to practice bravery, persistence, and patience, and demonstrating for all that children are not just recipients of our efforts, but participants in building a sense of place and who they want to be in the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

Spaces of Opportunity and the United States Forest Service

Contributed by Elise “Apple” Snider, education coordinator for the Southwestern Region of the USDA Forest Service

Standing in a circle on a rare overcast Arizona day, it was clear this would be the place for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service’s next outdoor classroom partnership. Spaces of Opportunity and their partners’ shared vision aligned with Forest Service values of interdependence, conservation, and diversity. With strongly rooted connections to community and place, proximity to schools, and ongoing urban agriculture, they even had a space in mind for an outdoor classroom as part of their master plan.

You might be wondering why the USFS would collaborate on outdoor classroom projects. We are primarily known as the federal agency that manages wildland fires and vast tracts of forested mountains. However, we are also members of the community and strive to provide equitable access to the benefits of nature, whether that is on a national forest or grassland, or closer to home. Outdoor classrooms can do just that in a joyful way! They provide hands-on, daily connections with nature for kids and families. This benefits both people and the land. Time in nature enriches children’s lives and learning, by supporting social and physical development, well-being, collaboration and creativity. And, because children who have positive experiences outdoors are more likely to want to protect nature as adults, time outdoors learning and having fun is crucial for the future of our planet, including the Forest Service and our public lands.

I want to offer my appreciation and thanks to Spaces of Opportunity, Nature Explore, and the many other organizations and community members for coming together and developing a shared vision for this outdoor classroom. May it be a space where all can learn, play and flourish.

Rostro Al Sol

by Virginia Angeles-Wann

This vital, beautiful story about how and why children participated in creating a mural for the Outdoor Classroom was written in Spanish, with additional words in Tohono O’odham. A rich and at times challenging intermingling of languages is integral to the story of Spaces and its community. An English translation is below.

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

El sur de Phoenix donde habitamos una gran comunidad mexicana y Mexicoamericana -entre otros grupos- se usa el español como primer idioma el cual está sujeto a la discriminación lingüística por ley en el estado de Arizona. Por esta razón, es importante que la clase de segundo grado y su maestra hayan decidido que una celebración tan milenaria no fuese olvidada y que su grupo tan diverso tuviese la oportunidad de cantar en español. Afirmar el derecho a retener y usar el idioma materno y sus expresiones culturales es importante para quienes somos parte de una de las nacionalidades oprimidas dentro de Estados Unidos de América. El respeto a la diversidad lingüística y cultural en uno de los estados con más problemas de discriminación y hegemonía cultural y lingüística sigue siendo un gran desafío.

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

Facing the Sun (translation)

by Virginia Angeles-Wann

[©Spaces of Opportunitiy]

In south Phoenix where I live, there is a large Mexican and Mexican-American community. For many of us, Spanish is our first language, which is subject to language discrimination by law in the state of Arizona. For this reason, it is important that this second-grade class and the teacher have decided that such a millennial celebration would not be forgotten. It was important for this diverse group of students to have had the opportunity to sing in Spanish. Affirming the right to retain and use one’s mother tongue with its cultural expressions is important to those of us who are part of one of the many oppressed nationalities within the United States of America. Respect for linguistic and cultural diversity in one of the states with a problematic history of discrimination with cultural as well as linguistic hegemony continues to be a great challenge.

After singing our lovely Son Jarocho, John and Fernanda ask the class what they would like to see on the wall of their Nature Explore Classroom. The answers are beautiful and diverse. There are those, like Shaheed, who want to see mesquite trees that they had studied as part of place-based learning. Lucinda wanted to see the western banded geckos that are part of the desert fauna. Danna brings the idea to paint butterflies and other insects. The list included flowers, plants, trees, and more trees. Fernanda and John take notes of all the ideas that the class gives.

The need and urgency to have images reflected in a mural in the middle of this space that represent the children from this community as whole and complete without omissions is present. Using the ideas offered by the class, Fernanda designed a mural with girls and boys with bronze, copper, and ebony skin showing the little people who will play and explore for many years to come in that urban/natural place. Children who will play jaranas under a mesquite singing in one language among many others. Children who will take care of pollinator gardens in order to contribute to the protection of harvest time butterflies, as monarchs are known in Michoacán. Monarchs who arrive just when the memory of our loved ones who have died is celebrated, not in “Coco” style, having to go through the U.S. customs of the underworld and produce “legal” documentation, because for the cultural empire of Disney even in death the souls of some people are excluded entrance to the other world by a status of artificial and absurd legality. Monarchs that cross three countries to remind us in the middle of the desert of how immortal nature is. The mural also reminds us of that immortality with Ta?ai (roadrunner), Do:da’ag (the mountains) and Ta? (the sun) that gives us life. Life that has been witnessed by the Tohono O’odham people in this great desert where borders were unknown. It also reminds us of this same fluid life in all its manifestations: animal, mineral, human and plant are important; that the smiles and games of all children are important without exclusion. In the end, when we account for what is sacred ground, what matters is how we did everything possible or impossible to care for and see that the imagination, passion, and curiosity of our little ones was allowed to grow. At the end of the day, what matters is seeing how our little ones and their voices and visions were defended and amplified. Ta? that embraces I’itoi in this mural—I’itoi the spiritual guide in the Tohono O’odham’s cosmovision—reminds us that there are many distractions and dead ends that lead nowhere to be avoided in order to live according to what sustains life, with what makes possible a future for new generations and achieve human equity without borders. For at the end of the road, when we will take a final look at the sun, before reaching the end of the labyrinth/life and make the last count, we will see if our contribution was or was not in favor of what gives and sustains life. Yes, it is in that last look at Ta? that bids us farewell and returns us to the womb of Mother Earth that we will be accountable to the seventh generation.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT