At first, Kaia Rolle, 6, appeared not to understand what the police officers were doing.

“What are those for?” she said, eyeing the zip ties the officers had brought to the school office in Orlando, Florida.

“It is for you,” one officer responded. As he tied them on, she started to sob: “No, don’t put handcuffs on. Help me!”

The excerpt above comes from body camera footage reported in the New York Times (Zaveri, 2020) from the day Kaia Rolle was arrested for throwing a temper tantrum and kicking a teacher in school. The footage goes on to show Kaia begging for a second chance as the police take her away. Her grandmother reports that Kaia is still working through the trauma of that day (Ardrey, 2021).

The over-disciplining of Black children is not new. In 2005, researchers at the Yale Child Study Center (Gilliam, 2005) reported that preschoolers were being expelled at alarming rates (6.2 per 1,000 children compared to 2.1 in K-12 settings) and that children of color were twice as likely to be expelled as *White children. News outlets from California to New York ran with the story (Lewin, 2005; Rivera, 2005) and the field of early childhood responded with attempts to curb this troubling trend. Head Start revised its program performance standards to prohibit expulsion linked to children’s behaviors (NCECHW, n.d.). Many states implemented similar policies in their publicly funded child care programs (Zinsser, 2021). Studies have been conducted to understand the impact of teacher bias on discipline tactics (Gilliam et al., 2016). The Center of Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation was established in 2019 to provide teachers, children, and families with access to support for challenging behaviors. And yet, while expulsion rates have gone down in the 17 years since this data was first released, the over disciplining of Black children remains stubbornly high with Black boys making up 40 percent of suspensions while accounting for only 18 percent of enrollment, and Black girls accounting for 53 percent of suspensions while making up only 19 percent of enrolled children nationally (Meek & Catherine, 2020).

There are no shortages of evidence-based programs and supports for child guidance (e.g. Gartrell, 2014; Hemmeter et al., 2007; Webster-Stratton, 2008), and yet these trends persist. This is likely because systemic racism is deeply entwined with definitions of what school is and what a good student looks like (Love, 2019). Black children are routinely held to adult standards while White children are given the freedom to behave like children (Epstein et al., 2017; Goff et al., 2014). The over disciplining of children of color has serious impacts on children and families, and can be the beginning of what some have called the preschool to prison pipeline (Wesley & Ellis, 2017). In her 2019 book, Bettina Love called on educators to engage in a “politics of refusal,” to stand firmly against the differentiated treatment of children of color. As an educator with several identities that typically hold positions of power and privilege (e.g. I am White, cisgender, straight, and hold an advanced degree), my hope is to respond to Love’s call with the urgency necessary to protect all children. The model I present in this article represents a shift in the way that I think about working with challenging behaviors, and centers the work of critical self-reflection and social justice alongside strategies for social-emotional learning and child guidance.

Labeling Behaviors

Exceptional teachers know that behavior is communication. When children engage in challenging behaviors, teachers seek to understand the intended communication and then teach the child pro-social ways to achieve their goals. This is a well-documented, evidence-based method that often leads to success (Hemmeter et al., 2007). If a child is pulling hair because they do not know how to enter play, teaching them to say, “Can I play?” is an effective solution. It is not, however, always so simple, and the ways that teachers assign meaning to behaviors may be connected to the over disciplining of children of color.

Behaviors are transactional in nature, in that they require at least two “partners in crime”: one partner to do the behavior, one to perceive it as challenging. Hair pulling seems obvious, but what about rough and tumble play? How do you know when somebody is being too loud? How long should a child be able to sit still and listen? These are subjective calls that are culturally bound. Teachers wield the interpersonal and disciplinary power (Collins, 2000) necessary to decide which behaviors are unacceptable and which get labeled as natural experimentations of childhood. The literature once again suggests that these decisions are tied to both individual and systemic biases, and children of traditionally marginalized backgrounds are more likely to have negative interpretations placed on their actions (Gilliam et al., 2016). Black children specifically are expected to behave more like adults than White children (Epstein et al., 2017; Goff et al., 2014). The teachers and police officers involved in Kaia’s arrest are unlikely to identify as racist but were likely influenced by societal standards that label Black children as dangerous or defiant.

Adapting a Model for Critical Reflection

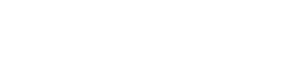

The adaptation of Ash and Clayton’s (2009) DEAL Model for Critical Reflection (Figure 1) is designed to encourage teachers to begin with critical reflections of both individual and systemic biases before designing an evidence-based behavior guidance plan.

ADVERTISEMENT

Teachers begin by describing the behavior objectively, being careful to stick to the facts without adding interpretation. By limiting interpretation early on, teachers reduce the impact of unexamined bias.

- Describe what the child is doing in objective terms, without adding labels or value to the behavior.

- When does this behavior occur?

- How often does this occur?

Figure 1. Adaptation of DEAL Model

Example:

Objective description: Kaia ran away from the group. When the teacher put her arm around her to physically bring her back to the group, Kaia screamed and kicked the teacher.

Interpreted behavior: Kaia hates listening to the teachers and was not paying attention. She is very physical and started kicking right away.

Critical self-reflection. Reflective capacity is central to infant and early childhood mental health consultation, which has been an effective tool in the reduction of preschool expulsion (Davis et al., 2007). When individuals engage in self-reflection, they begin to see how their experiences and personal beliefs influence the ways in which they interact with others. Rather than focusing only on what the child is doing, teachers begin to focus on how they are interpreting the behavior.

Is this a behavior that brings up big emotions for you? Why?

When have you seen other children do this? What was their race? How did you respond?

Could your previous experiences be leading you to make unfair assumptions about the child or the behavior?

Responses to these prompts help teachers to consider whether the child needs to change, or if they themselves need to shift their interpretations. A teacher might recognize that the labeling of the behavior as challenging is more about them than it is about the child.

Example:

When Kaia runs around or gets ready to hit, I feel scared. I do not want to be kicked and I start thinking about protecting myself. Last year we had a White girl named Julia who pulled hair and pinched, it really hurt. But if I am honest, when Julia got out of control I felt bad for her, I thought about her stress, and I worked to teach her new skills. I gave Julia the benefit of understanding, but with Kaia I just focus on my needs. I am treating these two differently and I wonder if it is connected to bias.

System analysis. After examining how personal experiences might influence the teacher’s interpretation of the behavior, it is important to consider a broader perspective. The following questions are adopted from Horton-Williams (2020) questions for ensuring equity in school discipline.

- What is the expectation? What should the child be doing instead of the challenging behavior?

- Why is this the expectation?

- Who decided that this expectation was necessary?

- Whose values are reflected in the expectations? Whose are erased?

- Who has difficulty meeting the expectation?

- What would happen if this expectation did not exist?

- How can this expectation be revised to accommodate all cultures/sets of values? Or, should this expectation be removed?

Example:

Growing up, I always had to sit crisscross applesauce with eyes on the teacher, and at home my parents wanted me to be calm and quiet, so that is what I expect of children. But maybe some kids are used to being able to move around more. Maybe they get uncomfortable when sitting for too long. Maybe if I let kids move their bodies, they would stay in the area and still pay attention.

Behavior support plan. After undertaking an honest examination of personal and systemic biases, move on to an evidence-based behavior support plan. As discussed, there are several strategies for supporting children to learn socially appropriate behaviors. The prompts below are adapted from the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning.

- What triggers the challenging behavior? What is happening in the environment when the behavior occurs?

- What happens after the behavior? What is the typical response to the behavior?

- Use your responses to determine the function of the behavior; what is the child trying to escape or obtain when engaging in this behavior?

- What strategies may work to prevent the behavior from occurring?

- What new skill do I want to teach the child?

- What will I do when the child uses the new skill? When they do not?

Next Steps. Whether the plan is working on shifting one’s perceptions, changing an expectation, or putting a behavior support plan in place, teachers should monitor progress and be prepared to reexamine their decisions.

Close examination of one’s history and closely held beliefs is a challenging but critically important step towards protecting all children. Teachers should consider how they will seek support as they engage in this process. Helpful resources might include:

- Regular meetings with coworkers, directors, or an early childhood coach to talk through the questions in the model. Inviting others to observe in the classroom can also help to bring in additional perspectives.

- Journaling to examine beliefs and perspectives.

- Attending an anti-bias training.

- Engaging in self-care activities such as getting enough sleep, spending time outdoors and eating well. This is challenging work, be kind to yourself!

Language related to racial identities continues to evolve, and the decision to capitalize the “w” in White is currently under debate by scholars. This decision follows the guidance of the Center for Study of Social Policy, which states, “We believe that is it important to call attention to White as a race as a way to understand and give voice to how Whiteness functions in our social and political institutions and our communities.”

References

Ardrey, T. (March 17, 2021). Kaia Rolle was arrested at school when she was 6. Nearly two years later, she still ‘has to bring herself out of despair.’ The Insider. insider.com

Ash, S.L. & Clayton, P.H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1, 25-48.

Collins, P.H. (2000). Black feminist thought. Routledge.

Davis, A.E., Perry, D.F., & Rabinovitz, L. (2007). Expulsion prevention: Framework for the role of infant and early childhood mental health consultation in addressing implicit biases. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41, 327-339. DOI: 10.1002/imhj.21847

Epstein, R., Blake, J., & González, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls’ childhood. Center on Policy and Inequality. dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3000695

Gartrell, D. (2014). A guidance approach for the encouraging classroom (6th ed). Wadsworth.

Gilliam, W.S. (2005). Prekindergarteners left behind: Expulsion rates in state prekindergarten programs. New York: Foundation for Child Development.

Gilliam, W., Maupin, A., Reyes, C., Accavitti, M., & Shic, F. (2016). Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions? ziglercenter.yale.edu

Goff, P.A., Jackson, M.C., Di Leone, B.A.L., Culotta, C.M., & DiTomasso, N.A. (2014). The essence of innocence:

Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526-545.

Hemmeter, M.L., Fox, L., Jack, S., & Broyles, L. (2007). A program-wide model of positive behavior support in early childhood settings. Journal of Early Intervention, 29(4), 337-355.

doi-org.ezproxy.library.wwu.edu/10.1177/105381510702900405

Horton-Williams, S. (2020). 10 Questions for ensuring equity in school discipline. School Leadership for Social Justice.

Lewin, T. (May 17, 2005). Research finds a high rate of expulsions in preschool. The New York Times. nytimes.com

Meek, S. & Catherine, E. (November 26, 2020). New federal data shows Black preschoolers still disciplined at far higher rates than whites. The Washington Post. washingtonpost.com

Love, B.L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. (n.d.). Understanding and eliminating expulsion in early childhood programs. eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov

Rivera, C. (May 17, 2005). Preschool expulsion rate is a surprise. Los Angeles Times. latimes.com

Webster-Stratton, C. (2008). The incredible years: Parents, teachers and children training series. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 18(3), 31-45.

doi-org.ezproxy.library.wwu.edu/10.1300/J007v18n03_04

Wesley, L. & Ellis, A.L. (2017). Exclusionary discipline in preschool: Young Black boys’ lives matter. Journal of African American Males in Education, 8(2) 22-29.

Zaveri, M. (February 27, 2020). Body camera footage shows arrest by Orlando police of 6-year-old at school. The New York Times. nytimes.com

Zinsser, K. (2021). 250 preschool kids get suspended or expelled each day: Five questions answered. phys.org

Carolyn Brennan is an assistant professor of early childhood education at Western Washington University. She began her career as a toddler teacher in a Reggio Emilia-inspired program and now teaches courses focused on infants and toddlers, families, behavior guidance and equity. Her research focuses on early childhood teacher preparation and supporting teachers to advance social justice in the classroom.

Related

ADVERTISEMENT